Introducing stamps as propaganda

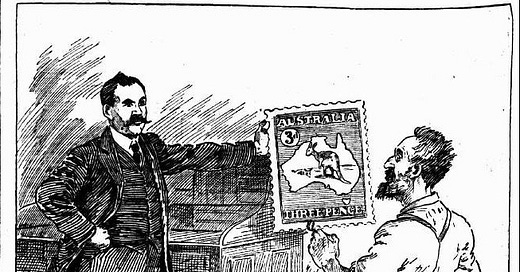

'A postage stamp is one of the best advertising mediums the country can have,' said Australian Postmaster General Charles Frazer in 1913, following a years-long debate about the nation's first issue.

Despite a more recent history compared to coins’ millennia of use, stamps have proven no less useful in influencing public opinion.

We’ll dive into the world of philatelic nation building with Australia’s first issue, released in January 1913, to better understand stamps’ influential nature and their ensuing interest among politicians. We’re starting here – and not, say, in Victorian Britain with the world’s first stamp, the “Penny Black”1 – because the Australian issue offers an immediate connection to other British dominions, including Canada. The 20th century saw these dominions attempt to shed their colonial past by redefining their national identity, which embraced a “civic, rather than ethnic, nationalism,” according to Canadian researcher Michael Maloney.

“Cultural symbols, including flags, anthems and television content, were common reference points as these governments grappled with colonial legacies and changing economic and political realities,” Maloney wrote in a 2013 article for Material Culture Review, Canada's only peer-reviewed scholarly journal dedicated to the study of material culture. “And yet while scholars of all three nations (Australia, Canada and New Zealand) have identified this pattern, very little in the way of comparative work explores just how similar or different such initiatives were.”

Stamps, he suggested, offer “one promising avenue for such exploration.”

WHAT’LL IT BE: A KANGAROO OR THE KING?

Now, let’s return to Down Under.

In January 1911, the Postmaster-General's Department (now a state-owned corporation called Australia Post) launched a public design contest to determine the subject and look of Australia’s first stamp. While the country gained independence from Britain a decade earlier, Australia remained a British dominion, and many of the submissions used royal themes in part or in full.

Among more than 1,000 submissions from roughly 530 artists, the winning design featured a full-face portrait of King George V with his gaze ennobled by a dashing moustache and beard.2 A kangaroo and an emu, both native Australian animals, flanked the monarch's effigy. The runners-up, a tie between two submissions, centred on the coat of arms and a kangaroo, respectively.

Officials moved forward with the George V design; however, in October 1911, another king-like figure came to the helm of the postal service, and 10 months of planning soon fell by the wayside.

In one of his first moves, the newly minted Postmaster General Charles Frazer scrapped the royal-themed design. His staff tasked the Victorian Artists Society to commission local watercolour artist Blamire Young,3 who began months of work, producing nearly a dozen essays, before the updated design shared Frazer’s vision of Australia.

Instead of the king’s ruggedly handsome head, Australia’s first issue – a 15-stamp definitive series sharing a common design with differently coloured denominations – featured a kangaroo within a silhouette of Australia’s map. The top of the design read “AUSTRALIA / POSTAGE,” marking the first time the country name exclusively appeared on a stamp.4 Overall, the design lacked any royal references.

Upon the stamp’s unveiling in April 1912 – nine months before its issue date – Frazer faced catty contempt in the court of public opinion. Mocked for what was considered an unsophisticated, unpatriotic and anti-British design, the concept drew criticism in the day’s popular media.

“Our postage stamps go all over the world; they become, in the course of time, a sort of national symbol; and it is therefore very annoying to find that our country is to be represented in the eyes of the world by a grotesque and ridiculous symbol, and that she will be a laughing stock even to childish stamp collectors of every nation,” reads a long-winded criticism in an April 1912 edition of Melbourne’s daily Argus newspaper.

Another rebuke published that month in Britain’s popular satirical magazine Punch called the design “as dull, flat, ugly and brainless as the dullest bourgeois could desire.”

“The result is simply childish; it represents a child’s tastes, a child’s mind.”

THE ‘ROO JOINED BY GEORGE V

On Jan. 2, 1913, nine months after the controversial design’s unveiling, the Postmaster-General's Department issued the first of 15 stamps in what became aptly known as the “kangaroo and map” series.5

The one-penny stamp marked the first regular issue since the country's six states – formerly British colonies – formed the Federation of Australia a dozen years earlier.6 Over the next three months, another 14 denominations, ranging from a halfpenny to £2, followed suit. In a show of national pride, the set was designed, printed and perforated in Australia.7

Half a year later, an election cost Frazer his post when the opposition Liberal Party toppled his Labour Party. The new government announced a new postmaster, Agar Wynne, who made quick work of Frazer’s design, which Wynne planned to replace with the top entry from the 1911 competition.

Australia’s long-awaited George V definitive, a one-penny stamp featuring his portrait alongside a kangaroo and an emu, finally entered the world on Dec. 8, 1913. Other denominations followed, and while many people awaited the withdrawal of the “kangaroo and map” stamps, they would frank mail alongside the George V definitives for decades to come.8

A NATIONAL DEBATE

Speaking in Parliament in August 1913, two months after he was ousted from the helm, Frazer explained his interest in the communicative power of the postage stamp.

“A postage stamp is one of the best advertising mediums the country can have. Every letter leaving our shores bears an advertisement of the country on its stamp. Stamps with the king’s head in the design are generally regarded as proper to communications from Great Britain. In designing our stamp, we put into it the outline of the coast of Australia. The stamp shows a white Australia, indicating the Commonwealth’s policy in regard to its population,” said Frazer, possibly referencing the country’s restrictive immigration policy.

“In the centre of the stamp is a kangaroo, an animal peculiar to Australia and common to every state of the union. That animal was drawn from the design which took the second prize.”9

In Parliament, Frazer then described the replacement design – the king’s portrait – as “execrable.” In his view, showing the British monarch on an Australian stamp failed to represent Australia’s national identity when the fledgling country needed it most.

Three months later, on Nov. 25, 1913, Frazer died of pneumonia at age 33. He fell half a decade short of the “kangaroo and map” design’s lifespan, which circulated for nearly four decades until 1948.

The design’s long-term use “underscores the political nature of Australia’s stamp production,” Maloney wrote in his 2013 article.

“This tension between national and imperial themes reflected a burgeoning ‘colonial nationalism’ not only in Australia but also in the British Empire’s other ‘white dominions,’” Maloney added. “Canada, Australia and New Zealand all endured awkward transformations from British settler societies to independent nations. Indeed, a growing body of work demonstrates that national identity in all three countries underwent significant reinterpretation during the 1960s.”

Frazer understood stamps as government-issued tools of communication representing the country at home and abroad.

“Moreover, as human-made objects that ‘reflect ... the beliefs of the individuals who commissioned, fabricated, purchased or used them, and by extension the beliefs of the larger society to which these individuals belonged,’ stamps are a valuable source of material culture,” Maloney wrote. “These small colourful pieces of paper, seen by citizens on an almost daily basis up until the late-20th-century explosion of electronic communications, are components of the print media, consequently making them potential instruments in the development of an ‘imagined community.’ Moreover … postage stamps are official products of governments keen to promote selected images domestically and internationally. They are thus useful, if often overlooked, resources for those interested in studying the construction of national identities.”

In the next edition of Power & Philately, we’ll rewind more than 180 years to the “Penny Black,” the world’s first stamp.

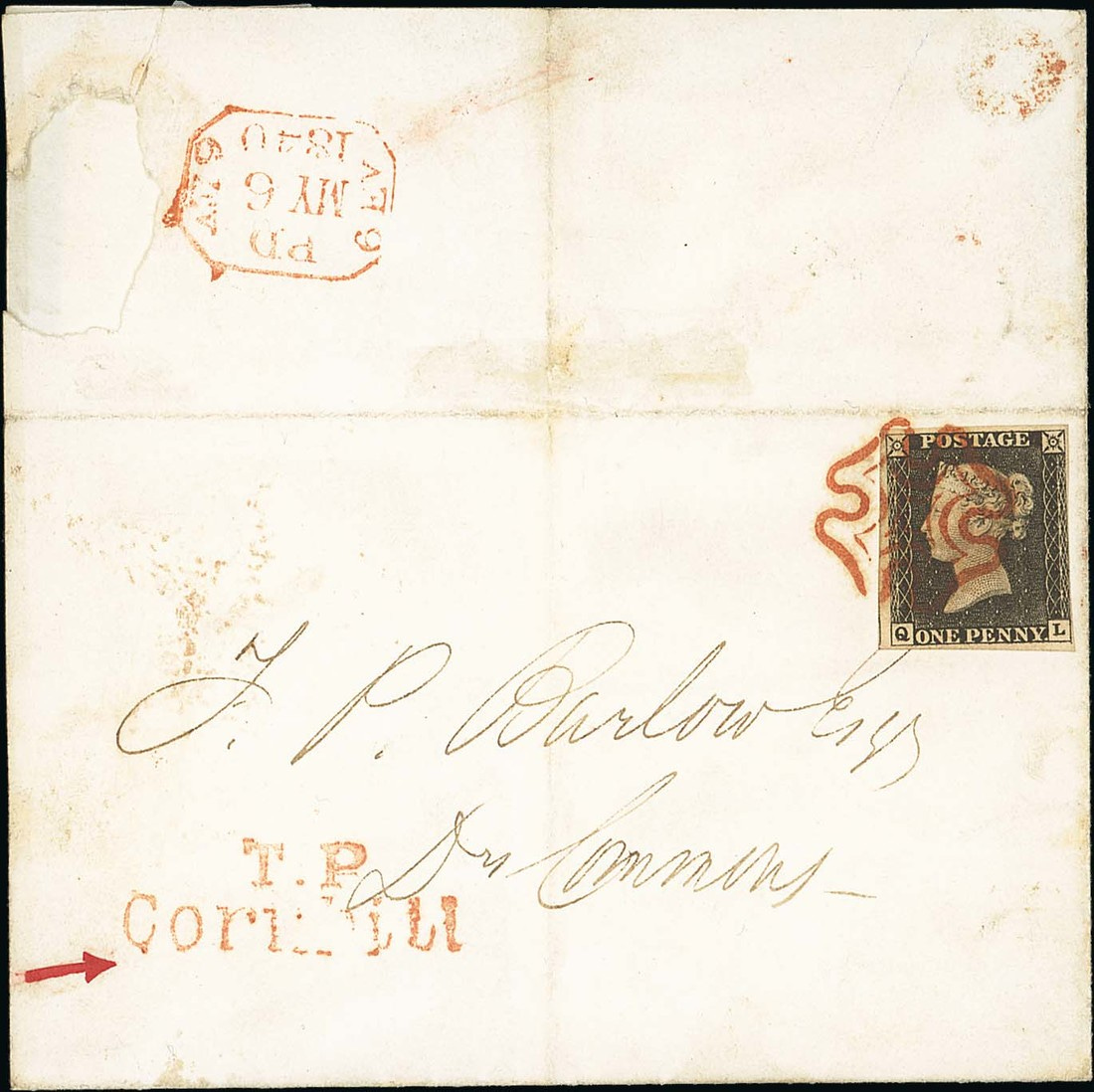

The “Penny Black,” as its name suggested, had a face value of one penny with a mostly black design featuring a left-facing portrait of Queen Victoria. Issued on May 1, 1840, the stamp became postally valid five days later; however, some pre-first-day covers franked with the Penny Black before May 6 are known to exist. One example, discovered in 1976 and dubbed “the world’s first cover,” featured a Penny Black with a Maltese Cross cancellation – another first – plus a postmark dated May 1, 1840.

“The Edwardian style – well-groomed sides, flamboyant moustache and a beard softly sculpted to a point – was popularized by King Edward VII and his son King George V,” said Stephen Wild, a manager at England’s Truefitt & Hill, the world’s oldest barbershop. “Both were immaculate dandies, always dressed in the height of fashion, and their beards followed that approach.”

While Blamire Young worked on several essays, it’s unlikely he produced the final “kangaroo and map” design. A contemporary letter to the editor of the Daily Telegraph written by acclaimed architect William Hardy Wilson, Young’s friend, claimed the artist’s design “was not approved of.” The final design, Wilson wrote, “shows a crude and commonplace idea of decoration that could not possibly have been produced by an artist.”

Before Australia’s first issue in 1913, its six states – former British colonies – issued stamps inscribed with their respective name (Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, South Australia and Western Australia).

Most collectors simply refer to them as “the ‘Roo issues.”

In 1902, a year after its federation, Australia issued “postage due” stamps—special issues used to indicate insufficient postage. Postal clerks would affix a “postage due” stamp to underpaid mail to note the remaining fee would need to be paid by the recipient.

The “kangaroo and map” designer may be lost to history, but they were undoubtedly Australian (some researchers believe the collaborative design borrowed elements from Blamire Young, Charles Frazer and one of the submissions from the 1911 competition). Melbourne printer James Bradley Cooke printed the series while engraver Samuel Reading, also of Melbourne, prepared the die.

The “kangaroo and map” stamps saw 38 years of use while the George V definitives circulated for 23 years.

Charles Frazer’s comment about the kangaroo, drawn from the second-place winner in the 1911 competition, confirms the collaborative nature of the “kangaroo and map” design.

I had never heard of this before. This was extremely interesting