Politics and the Penny Black: The power of banal nationalism

Among the many symbolic actions and tangible artifacts serving under the umbrella of 'banal nationalism,' stamps and their subtle messages have long played a significant role in shaping nationhood.

This is the final story in a two-part series on the ‘Penny Black,’ the world’s first adhesive postage stamp. You can read part one here. Both stories belong to an overarching multi-part introduction series slated to conclude with the next edition of Power & Philately—but more on that later.

At 1,888 words – just 688 more than my recently embraced “sweet spot” – the story sitting before you remains a tad long owing in part to my apparent lack of self-control as a writer. But then again, it’s my newsletter; who’s to say my whimsical flair is unbecoming of a professional when I’m only looking for a bit of fun anyway?

I’ll level with you: I write succinct copy every day of my life. It’s my job. P&P, on the other hand, explores facets of the English language impractical for print-based venues—and most online ones for that matter. (My newsletter is not, despite your highest hopes for me, a “hustle.” I fall more in line with the anti-work ethic espoused by Friedrich Nietzsche.1 But I digress.)

You should consider P&P a creative outlet through which the writer – that’s me – frees himself from the shackles of traditional print journalism to embrace the pageantry of flowery language and the abstract poetry of long-form storytelling on the Internet.

Thank you, dear readers, for following these regular outbursts of creative freedom and abiding by my desires in all their insufferable prolixity.

Proof of the Penny Black’s success lies in its legacy: the vast majority of the stamps issued in the 183 years since then have imitated its innovative style in the utmost form of philatelic flattery.

In a succinct, almost sexy manner, the simple yet effective design balanced the stamp’s small size with all the necessary information, including its postal purpose, value and country of origin.2 While more explicitly stated on modern stamps, it’s a template still borrowed by today’s postal services—and for good reason.

Stamps have long lent their myth-making capabilities to nation-building endeavours at home and abroad while serving as a form of soft diplomacy in the global war of ideas. Britain advanced its empire on the backs of these seemingly humble postage stamps, different iterations of which soon became a mainstay on mail worldwide. Essentially receipts, these small government documents spread far and wide to perform a valuable role beyond their practical postal duties: they propagated propaganda.

In championing the ideals of their issuing nations, stamps covered everything from their respective country’s history and past achievements to current politics and contemporary culture, according to retired anthropologist and professor emeritus James Grayson.

“As such they are an important documentary resource for the study of a state and a nation,” Grayson wrote in the first chapter of Stamps, Nationalism and Political Transition.3 “A postage stamp is more than just a scrap of paper indicating that the appropriate fee has been paid for the carriage of a postal item from one place to another. A state or some other political entity uses stamps to project onto the world stage a positive image of itself and domestically to affirm itself and its values.”

He likened it to a form of “banal nationalism,” a concept coined by fellow professor emeritus Michael Billig, a social psychologist, in his 1995 book of the same name. The concept centres on covert cultural symbols and practices – hokey things such as national anthems, flags and holidays – through which governments can impose or reinforce a sense of national identity.

“This process ensures that citizens’ sense of nationalism becomes endemic—ready to be called upon at times of national threat or crisis,” Grayson wrote, adding its routine nature sometimes makes banal nationalism difficult to detect—and resist.

A SMALLER WORLD WITH STAMPS

Part of the postage stamp’s banality is owed to its virtually ubiquitous nature from the second half of the 19th century through the 20th century.

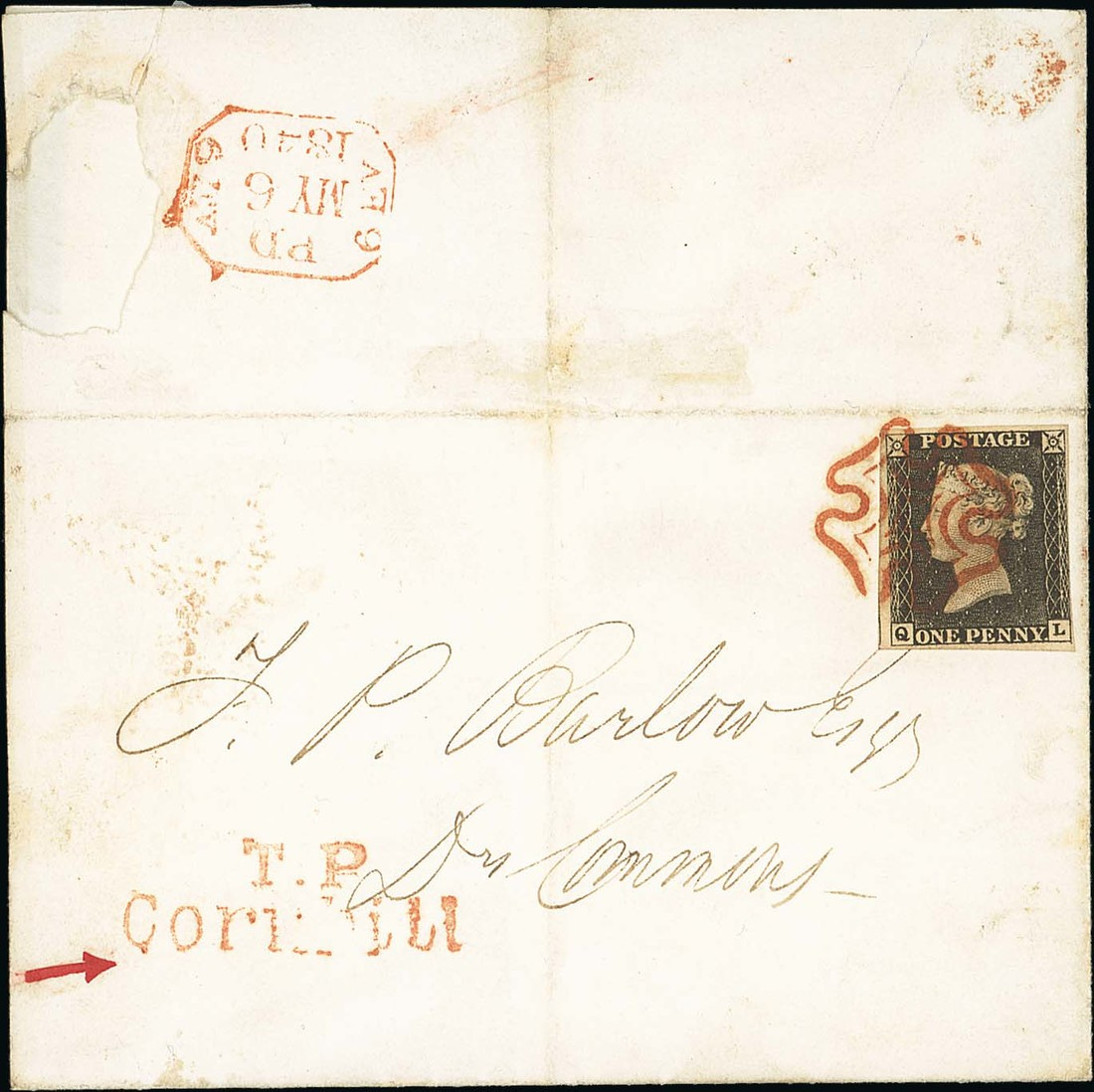

Following Britain’s 1840 postal reforms, anyone who wanted to participate in the marvel of global communication – even royals – needed to pay an up-front fee in the form of a postage stamp. The person sending the mail proved their payment by affixing the stamp to another new invention, the envelope (which postal historians have dubbed the “cover” because it encloses, or covers, a letter).

From the outset, the Penny Black revolutionized mail delivery in Britain by facilitating the reformed system, and the advent of envelopes made people more comfortable with mailing sensitive information. Year-over-year letter volumes more than doubled following the stamp’s issuance.4

Soon known as a reliable mail service for personal, social and commercial purposes, the system set the stage for the empire’s colonies and dominions – and indeed most other countries – to follow suit with their own stamps. Within 15 years of the Penny Black, nearly 60 other countries, kingdoms and colonies, including the colony then known as the Province of Canada, formed stamp-issuing postal systems based on the British model. As their nation-building designs travelled the world, these first issues spurred the global proliferation of post offices, mailboxes and dispatches.5

Across her 63-year reign, Queen Victoria graced the stamps of nearly every British imperial possession—a legacy mirrored by Queen Elizabeth II, whose face later appeared on more stamps than anyone else in history.6 Over the years, these issues symbolized to the world the monarchy’s strength and resilience in Britain and across the empire (and in more recent years, the Commonwealth of Nations).

THE TRICHOTOMY OF SIGNS

On top of facilitating the ever-expanding global postal system, the world’s first stamps offered a new medium through which governments could address the public.

All stamps since the Penny Black have held vast communicative power with most issues printed millions or many billions of times. All of them feature, in some form, self-glorifying images espousing the nationalist tenets of the respective stamp-issuing country.7

The paper-based medium has long been “a piece of national advertising more widely circulated than any other,” according to art historian Nikolaus Pevsner, writing in Country Life magazine to mark the Penny Black’s 100th anniversary in 1940.8

Now with nearly 200 years of use, the apparently trivial and ephemeral postage stamp continues, at its best, to speak to the hearts and minds of the issuing country. (At its least, it’s a bullhorn for some rogue issuer and their vision for the country or world.) Regardless of their intention – mere political rhetoric or legitimate voice of the public – stamps offer insight into the goings-on of past and present simply by virtue of their long-term, widespread use. Based on their exceptional popularity, which increased the stakes for their issuers, they can be trusted as a relatively reliable source of said insight: those designs and their messages mattered a whole lot to the people creating them.

Spread across the globe as people sent messages to one another, these multitudinous bits of gummed paper carried their own compelling messages in the form of signs.9

U.S. philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce, who before his 1914 death earned the title of “the father of pragmatism,”10 developed a three-part typology he dubbed “the trichotomy of signs.” In it, he classified signs as icons, indices and symbols; usually, they’re tied together in an intricate combination of all three types.11 Peirce’s work remains a significant resource in the world of semiotics, and it's something to which I’ll frequently refer in the pages of P&P.

Stamps typically provide three semiotic messages, two self-referential ones and a quantitative one, according to late U.S. professor Jack Child, who died in 2011.

“At deeper levels of semiotic meaning, messages common to most stamps are carried by features of design,” Child wrote in his 2008 book Miniature Messages: The Semiotics and Politics of Latin American Postage Stamps.

Specifically, he referenced a stamp’s colour, typography, layout and “any representational drawings, engravings, photographs or other graphics,” all of which “deliver increasingly sophisticated messages of a cultural, historical, political or economic nature.”

A stamp’s self-referential messages include something to identify its practical purpose – that of a stamp – plus something to note its country of origin. The quantitative message centres on the stamp’s face value, which confirms the sender properly paid the correct postal fee, its most immediate purpose. While the self-referential messages comprise indices, the stamp also features symbols (letters and numbers) plus icons (pictures and images).

While they’re the entire focus of Power & Philately, a stamp’s iconic elements form the least essential – or as some would argue wholly unnecessary – part of the design.

“Here it is worth noting that there is no reason why postage stamps should carry any imagery or decoration whatsoever,” Australian historian Humphrey McQueen wrote in a 1988 study,12 adding stamps are “not merely utilitarian.”

“The inclusion of images has meant that the postage stamp was supposed to do more than prove that the charges for delivery have been met.”

THE MYTH-MAKING CONTINUES

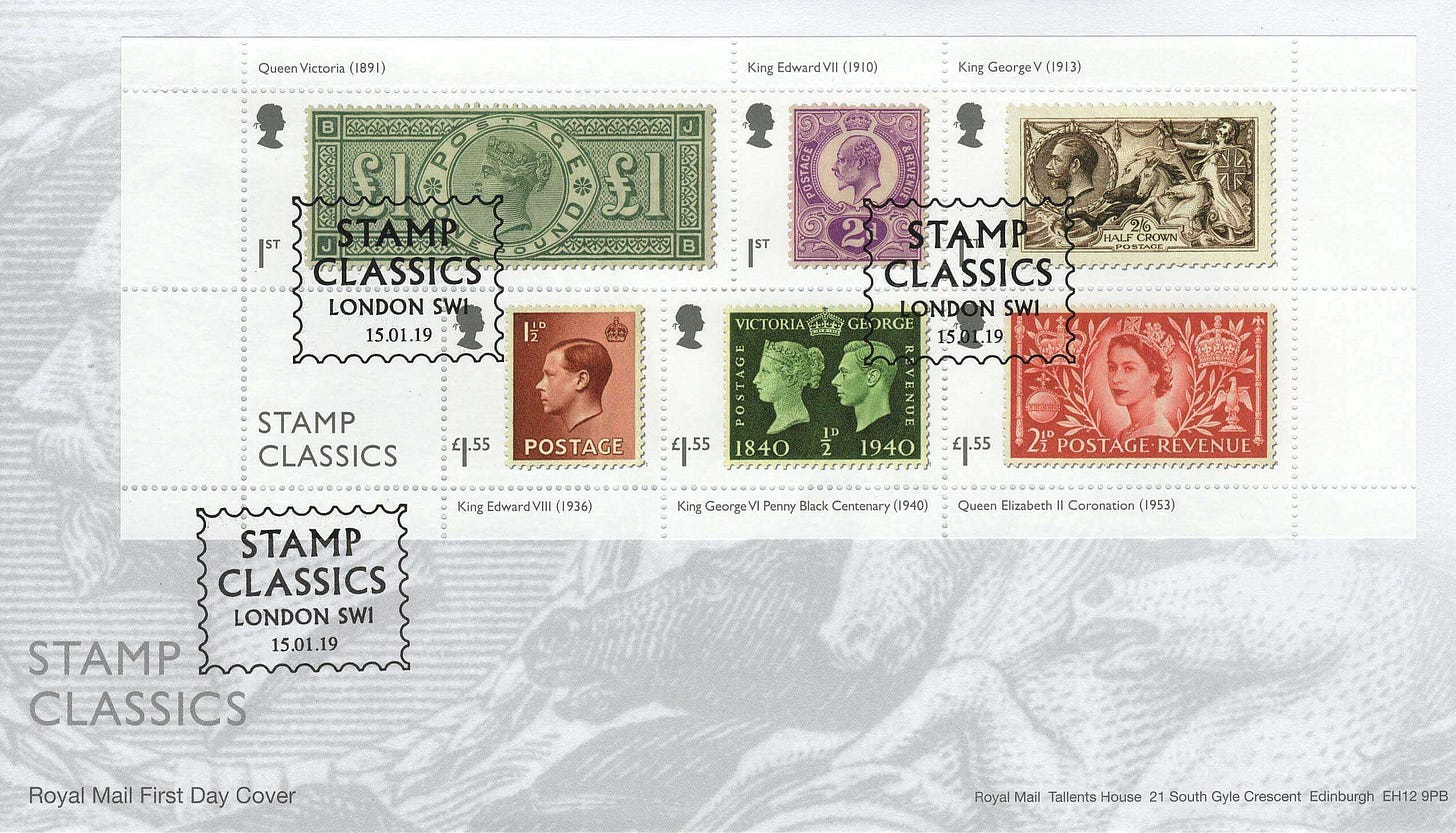

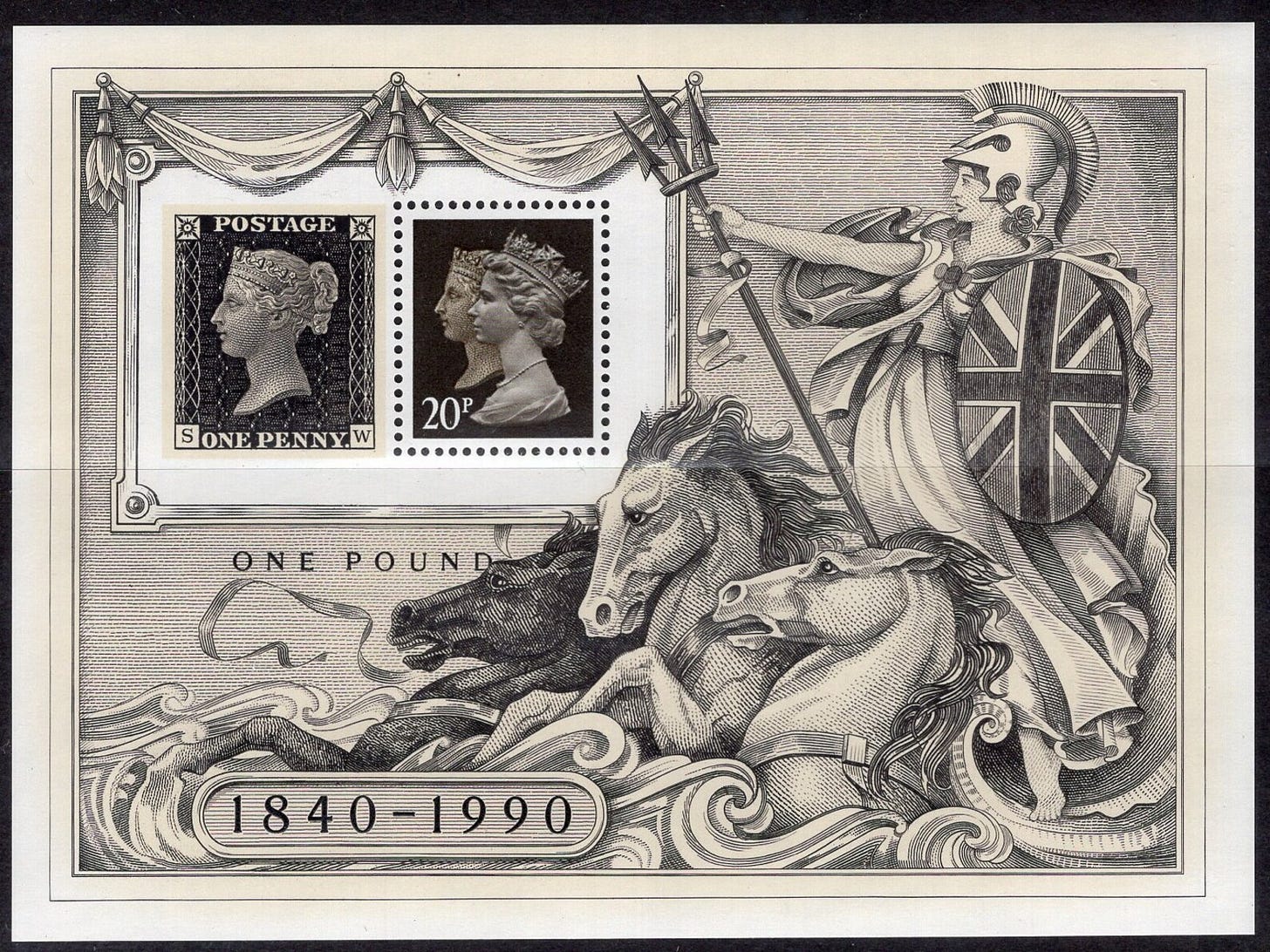

Since Queen Victoria appeared on the Penny Black, another five British monarchs – Edward VII, George V, Edward VIII, George VI and Elizabeth II – have graced the nation’s definitive stamps.

“The definitive stamp has become a recognizable symbol of each reign,” said Royal Mail Chief Executive Officer Simon Thompson.

Earlier this month, the United Kingdom’s Royal Mail unveiled the first definitive stamps to feature King Charles III, the late queen’s son, who ascended the throne after her death last September. Four differently coloured values will enter circulation on April 4 with a common design.

The Charles III definitive features an adapted version of a portrait created by British sculptor Martin Jennings for the obverse of new U.K. coinage showing the monarch facing left. The use of the numismatic design continues a tradition dating back to the Penny Black, which borrowed a diademed portrait of Queen Victoria from an earlier medal marking the monarch’s visit to the Guildhall, a centuries-old town hall in the heart of London.

Approved by the monarch – a process followed for all British stamps – the design lacks the crown and jewellery donned by his mother and some earlier monarchs.13

“The guidance we got from His Majesty was more about continuity and not doing anything too different to what had gone before,” Royal Mail external affairs director David Gold told the Guardian. “There is no embellishment at all, no crown, just simply the face of the human being on the plain background, almost saying: ‘This is me and I’m at your service,’ which I think in this modern age is actually rather humbling.”

The new king told postal officials “not to try to be too clever or to veer off into some different direction but very much to keep that traditional image that we’re all very much used to,” Gold told Reuters in another interview.

In the next edition of Power & Philately, we’ll look at Canadian stamps and their myth-making motivations through the 172 years between that country’s first issue and the present day.

In what British scholar Keith Ansell-Pearson called Friedrich Nietzsche’s least studied work, The Dawn of Day lays out the German philosopher’s thoughts on morality and its effects on society in 1881. As with most of Nietzsche’s notoriously difficult and occasionally contradictory tomes, The Dawn of Day is “controversial to the marrow,” according to 20th-century philosopher Walter Kaufmann. In it, Nietzsche criticizes traditional morality, both secular and religious, for its negative influence on art, culture and human behaviour. Less of an attack on morals per se and more of a takedown of tradition, The Dawn of Day calls for embracing one’s individuality through personal freedom and self-expression. It suggests replacing those traditional external values, which can stifle creativity and fall askew of one’s instincts and desires, with a set of self-determined beliefs.

What we now call hustle culture, one of the areas Nietzsche explores in the book stems from what he describes as the “eulogists” of work: “Behind the glorification of ‘work’ and the tireless talk of the ‘blessings of work’ I find the same thought as behind the praise of impersonal activity for the public benefit: the fear of everything individual. At bottom, one now feels when confronted with work – and what is invariably meant is relentless industry from early till late – that such work is the best police, that it keeps everybody in harness and powerfully obstructs the development of reason, of covetousness, of the desire for independence. For it uses up a tremendous amount of nervous energy and takes it away from reflection, brooding, dreaming, worry, love, and hatred; it always sets a small goal before one’s eyes and permits easy and regular satisfactions. In that way a society in which the members continually work hard will have more security: and security is now adored as the supreme goddess.”

For both Nietzsche and me, work’s value lies in the application of creativity – the flourishing of the individual – rather than the vacuous Puritan approach of simply working for work’s sake.

An imperforate issue cut from 240-stamp sheets by postal clerks, the average Penny Black measures about 4.8 square centimetres (20 millimetres by 24 millimetres) depending on its margin size.

Published last year, the interdisciplinary 22-chapter book Stamps, Nationalism and Political Transition features about two dozen contributing authors, including James Grayson, plus editor Stanley Brunn. A retired U.S. professor, Brunn recently spoke about stamp iconography in fascist regimes at the 12th Winton M. Blount Postal History Symposium, which I was happy to (virtually) attend. This year’s theme centred on political systems, postal administrations and the mail, and it proved quite helpful in developing Power & Philately.

Meanwhile, the world grew smaller. Stamps and other contemporary technological advancements – namely steamships, railways and the telegraph – offered unprecedented levels of interconnectedness in the first steps toward the “global village.”

For collectors interested in first issues as an area of specialization, the First Issues Collectors Club, an American Philatelic Society affiliate, takes a global approach to the hobby by only focusing on the first issues of all nations, provinces, cities, armies and other stamp-issuing entities. The roughly 100-member club, currently headed by Montréal-based President Louis Laflamme, publishes a regularly updated catalogue of new issues plus a quarterly journal.

Canada featured Queen Elizabeth II on more than 90 definitive and commemorative stamps in various formats throughout her 70-year reign. Her face also appears on more British stamps than anyone else with hundreds of billions of them printed for use on mail.

The themes of these myth-making messages have evolved over the years. The vast majority of 19th-century stamps carried royal, heraldic or classic government themes; however, the turn of the century marked a watershed moment in which many countries began celebrating their distinct national identities by recognizing their own anniversaries and leaders.

Nikolaus Pevsner authored “Style in Stamps: A Century of Postal Design,” in the May 4, 1940, issue of Country Life magazine. Nearly a century later, it remains a delightful read.

Signs embody semiotics, the study of meaning, its creation and its communication via message-signalling icons, indices and symbols (the three types of signs first described by U.S. philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce). In the semiotic sense, a sign refers to any symbol representing something other than itself.

Pragmatism, a school of thought emerging from the 1870s United States, grew to become that country’s most dominant philosophy by the turn of the century. With a far-reaching influence on art, education, law, politics and religion through the early 1900s, pragmatism contrasts idealism’s potentially abstract theories, principles, values and goals with a more practical, empirical approach to solving problems and understanding the world. I’m no philosopher, but from what I understand, a pragmatist will ignore ideals and social norms to instead focus on concrete realities.

It’s similar to modern-day philosopher Curtis Yarvin’s suggestion democracy has failed and should be replaced by what he first called formalism. “To reformalize, therefore, we need to figure out who has actual power in the US, and assign shares in such a way as to reproduce this distribution as closely as possible,” Yarvin wrote in 2007 about his new ideology, which has since gained considerable popularity among the New Right. “Of course, if you believe in the mystical horseradish, you’ll probably say that every citizen should get one share. But this is a rather starry-eyed view of the US’s actual power structure. Remember, our goal is not to figure out who should have what, but to figure out who does have what.” It echoes the contrast between pragmatists, who focus on the world as it presently exists, and idealists, who represent it as they believe it could or should exist.

Perhaps this 2018 quote from Pennsylvania Democrat John Fetterman, who expertly shitposted his way to the U.S. Senate earlier this year, will enlighten you further: “I’m not pro-fracking. But sometimes, there’s got to be some pragmatism.”

“In layman’s terms,” according to late U.S. professor Jack Child, “the three elements of the typology can be defined as follows.” An index serves as a “pointer taking the viewer somewhere. An example would be smoke, which is an index to the fire that released it.” An icon refers to a “graphic pictorial representation such as a picture, a design, or a photograph. It can be observed for its own aesthetic sake or, more important for our semiotic analysis, analyzed to see what the message of the picture is.” Lastly, a symbol is a “conventional sign in which elements stand for something else. Thus the symbol ‘$’ stands for dollar, and the post horn is a common symbol for postal service.”

The 1988 study, “The Australian Stamp: Image, Design and Ideology,” ran in Australia’s Arena journal (issue #86).

Northern Irish historian Keith Jeffery explains further in a 2006 issue of the Journal of Imperial & Commonwealth History: “While on her head the queen wore a regal tiara, an ‘imperial crown’ watermark was used from 1880. Identifiable only on the reverse of the stamp, this reflected Queen Victoria’s much more visible change of status to ‘Empress of India’ from 1877. On the stamps of her three male successors, Edward VII, George V and George VI, the practice changed. Embodying an intensification of imperial imagery in their stamps, the monarch’s head was consistently surmounted or associated with the imperial crown. In 1952 the practice changed again. Apart from Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation stamps of 1953, on which both the imperial and state crowns appear, the crown disappeared almost entirely from British stamps. Between 1952 and 1966 Queen Elizabeth, like her great-grandmother, was invariably depicted wearing a tiara, but since then some commemorative issues have used a bareheaded version of the queen’s profile. The removal of imperial and royal iconography from British stamps perhaps stems from a conscious demystification of monarchy, but it also undoubtedly reflects its increasingly diminished status over the second half of the twentieth century and beyond.”

Erudite 2 parter! Banal nationalism has often been in my thoughts as I practise as a collector of these receipts.