The world's first stamp: Politics and the Penny Black

Large crowds of Victorian-era Brits clamoured for an opportunity to buy the Penny Black, 'an innovation equal to today's iPads and iPhones,' according to U.S. professor Catherine Golden.

This is the first story in a two-part series on the ‘Penny Black,’ the world’s first adhesive postage stamp,1 plus the follow-up ‘Twopenny Blue’ and ‘Penny Red.’ I’ve divided this edition because I’m skeptical most people would effectively consume all this porridge-thick prose in one fell swoop. Even those big-brained readers with IQs exceeding my word count could take 10 or more minutes to properly consume it, what with all its footnotes and requisite trips to the dictionary. (Words hold distinct meanings based on their context; even synonyms have subtle differences distinguishing them from their counterparts. While most English words are polysemous,2 each of them means something specific depending on how it’s used. I’ve yet to regret cracking open a dictionary upon encountering a strange word or an uncertain context.)

Back to my embrace of the sweet spot, about 1,200 words—nothing short and lifeless like what a hack might publish, and nothing so long it diminishes your few fleeting moments of daily liesure to a form of funless drudgery. Late ’70s Canadian mythology tells us we’re here for a good time (not a long time), so let’s get on with uncovering the government’s occasionally underhanded nation-building endeavours via the unassuming postage stamp. At its best, Power & Philately should serve its readers akin to those special flat-topped glasses from John Carpenter’s They Live.3 Right? Let me know about this and other matters (e.g., the self-absorbed nature of a more than 250-word subhead) in the comments below.

Stamps tell stories, and the long-running spiels date back nearly two centuries.

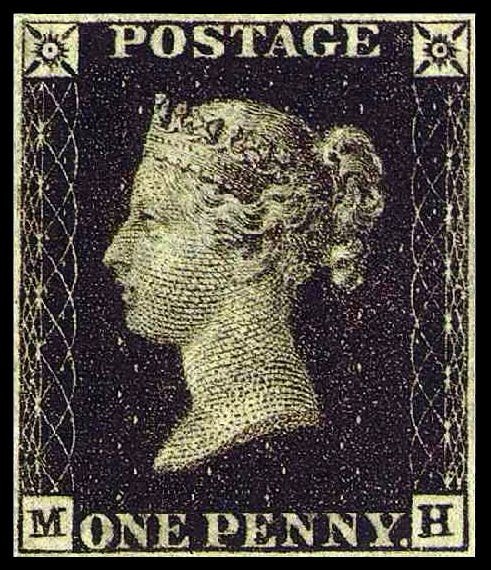

This May marks 183 years since the story of stamps began, in effect, with the “Penny Black.” It’s a tale of the early global village connected by humble technology—a 20-millimetre-by-24-millimetre piece of woven paper conceived, designed, engraved, printed and sold in five short months.4 While the stamp played a central role in the 19th-century communication revolution, its design held intrinsic communicative power as one of the Victorian era’s most widely visible artifacts.

About 2,500 years after those startup-minded Lydians struck the world’s first coins, the top British minds developed the first stamp to facilitate their newly reformed postal system. The small servile issue, inked with the monarch’s portrait, served as proof of payment (in this case, a one-penny flat rate) to send a letter weighing up to 14 grams anywhere in Britain.5

The reforms conceptualized by British schoolmaster Rowland Hill took form with the launch of the "uniform penny post" in January 1840, four months before the Penny Black first circulated. While the old ways of delivering mail proved costly and complex due to an unwieldy workforce and a lack of fiscal control, the flat rate allowed letters to be sent anywhere in Britain regardless of the distance.

Without further ado, the uniform penny post boosted mail volumes: 112,000 letters, four times the usual amount, passed through the General Post Office in the capital of London on the first day of service.6

A few months later, the Penny Black encouraged people to send still more letters, and the revolution gained steam. Large crowds clamoured for an opportunity to buy “an innovation equal to today’s iPads and iPhones,” according to U.S. professor Catherine Golden.7

Over the next year, people in Britain mailed about 169 million letters—up from just 76 million in 1839.8 By 1860, the British mail stream took in 564 million letters and more than 80 million other items, including newspapers, magazines and books.9

The postage stamp ushered in a new era of global communication, and their near-ubiquitous use presented an unprecedented opportunity for 19th-century nation builders. The Penny Black set the stage for stamps as nation-building tools in countries around the world. By 1853, a little more than a decade after the Penny Black revolutionized mail delivery, 44 countries, including Canada (then known as the Province of Canada), launched stamp-issuing postal systems based on Hill’s model.10

“Rowland Hill understood very clearly that there are hidden, non-monetary values to having a good postal system—that they bind the community together, they help people, they increase literacy,” British writer Chris West, who authored the 2012 book First Class: A History of Britain in 36 Postage Stamps, said during a keynote presentation at the 2013 Maynard Sundman Lecture. “They did in the Victorian days, anyway, because people were encouraged to learn to read and write so they could communicate. It made life more pleasant in lots of ways that weren't reflected in the monetary values of the stamps, and this is still a live issue today, I think.”

THE QUEEN’S LONG REIGN

As an 18-year-old Queen Victoria ascended the throne in 1837, few people predicted her reign would reach an unprecedented 63 years and 216 days—a record only surpassed by her great-great-granddaughter in 2015.

More than 80 stamps mirrored the Penny Black’s portrait throughout the queen’s reign, upholding Britain’s national and imperial identities at home and abroad. Accompanied by a white-line machine-engraved background plus a simple crown watermark for forgery prevention, the design graced every stamp issued during Victoria’s reign.

“To this day England has never thought it necessary to identify her stamps with more than her sovereign’s portrait,” U.S. professor Donald Reid wrote in his 1984 study, “The Symbolism of Postage Stamps: A Source for the Historian.”

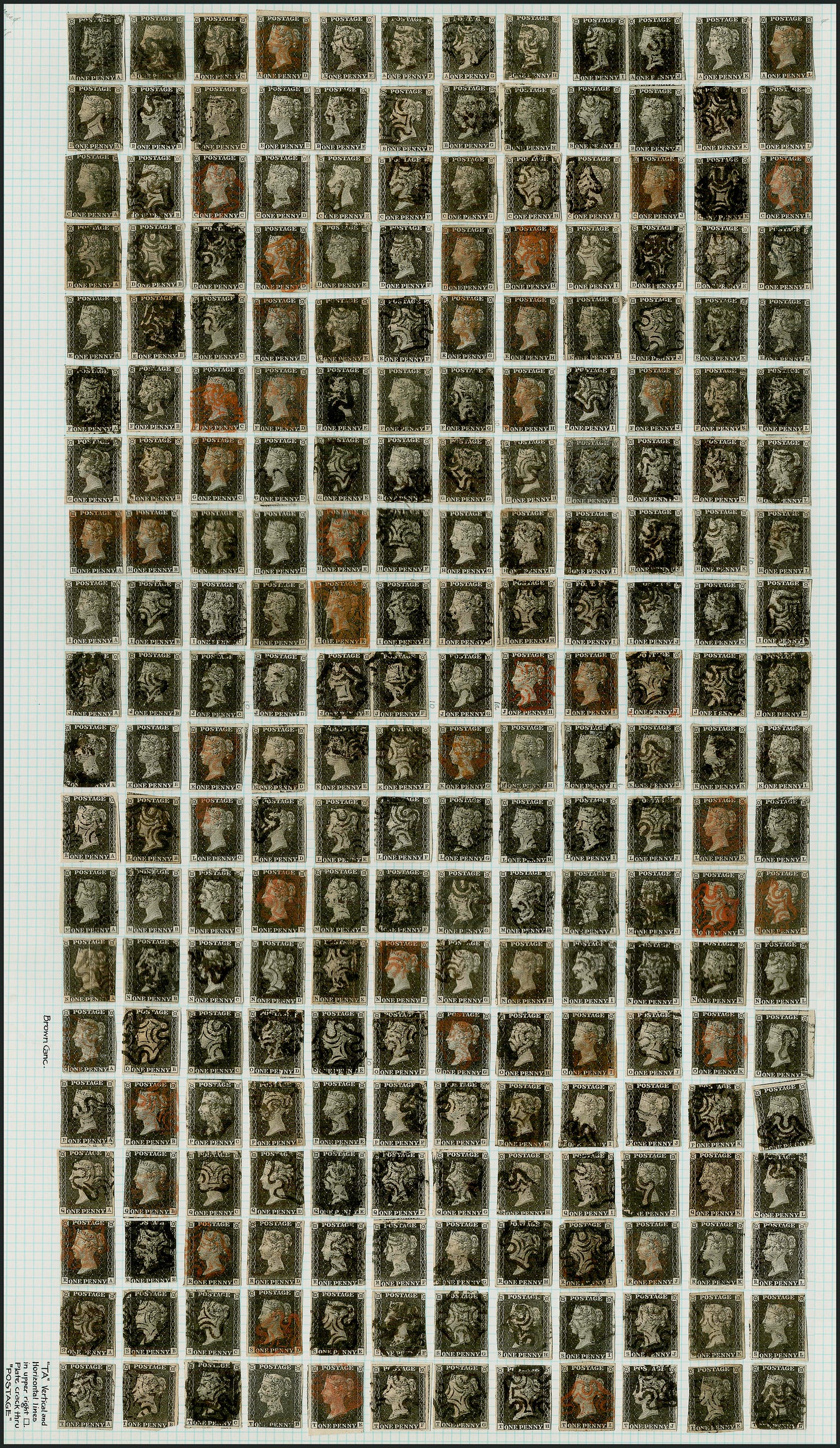

The Penny Black saw a one-year print run with about 68 million stamps produced from 11 plates. It became postally valid alongside the “Twopenny Blue,” the world’s second stamp, whose short print run saw only 6.46 million stamps produced from two plates over the following four months. The Penny Red followed with about 21 billion stamps printed from 1841-79.

All three issues showed the queen’s head with the words “POSTAGE” along the top and either “ONE PENNY” or “TWO PENCE” along the bottom, indicating the stamp’s function and value, respectively.

The design – as with all British stamps to this day – used the monarch’s portrait as its only indication of the issuing country, a legacy owing to Britain’s pioneering development and use of stamps.

“In effect, the designers of this first stamp had hit upon an excellent balance between the economy of small scale, and the minimal size for the required information,” U.S. professor Jack Child wrote in his 2008 book Miniature Messages: The Semiotics and Politics of Latin American Postage Stamps, referencing the “index, icon, and symbol, as well as the monetary value of the stamp.”

The design remained mostly untouched on future definitives.11 The only changes came with the colour (in 1841); the addition of perforations and check letters12 (in 1848 and 1858, respectively); and updates to the value (in several years). The portrait’s youthful image contrasted the occasionally updated likenesses on Britain’s coinage, which showed the queen's age as late as the 1890s, just a few years before she died.

In the next edition of Power & Philately, the series’ final story will take a closer look at the semiotics of the Penny Black.

Before the advent of the adhesive postage stamp in May 1840, postal clerks used various postmarks to track letters entering the mail stream. Originally called “Bishop marks,” they came from the mind of British Postmaster General Henry Bishop and predated the Penny Black by 179 years (just a few years shy of the timespan between the Penny Black’s issue date and today). Pre-reform postal rates partly depended on the distance a letter would need to travel for delivery; typically, recipients were responsible for paying the rate, often a complex and costly process as I reported for Canadian Stamp News in 2018 (“Expensive rates, confusing routes spell need for change,” Vol. 43 #15). Research from prolific philatelic writer Ken Lawrence, of Pennsylvania, shows earlier non-adhesive stamps and stamp-like ephemera (paper wrappers, ink seals, copper metal tickets and more) saw use in Austria, France, Greece, India, Sardinia (present-day Italy), Scotland, Spain, Sweden and other countries before the Penny Black.

According to Oxford Bibliographies, polysemous words are associated with two or several related senses (such as “a straight line,” “washing on a line” and “a line of bad decisions”). Less common, monosemous words are associated with a single meaning (such as chisel, dahlia or iguana, according to another 1988 source). Homonymous words, on the other hand, are associated with two or several unrelated meanings (such as bat, which could refer to the offensive tool used to score runs in baseball or the winged animal of the same name; write and right offer another example despite the different spelling).

It’s a metaphor. I’m not suggesting we’re subservient to an elite ruling class of shapeshifting aliens who conceal their true identity while using subliminal messages to encourage our falling in line with their agenda. As the saying first attributed to Sigmund Freud in 1950 goes, “A cigar is sometimes just a cigar” (and it follows a stamp is sometimes just a stamp). Regardless, stamps provide great insight into the myth-making motivations of our nation-building ancestors.

Douglas Muir, the former senior curator of philately at the U.K.-based Postal Museum and a Roll of Distinguished Philatelists signatory, authored an exceptional digital book detailing the printing processes for British stamps. The London firm Perkins, Bacon & Petch printed the Penny Black in 240-stamp sheets using intaglio printing and flat-bed presses before applying the gum with brushes to the back of the sheets.

For reference, a typical envelope weighs about 6.75 grams. Stuffed with just one roughly 4.5-gram sheet of paper, the cover would hold nearly 11.25 grams together with its contents. Eight days after Britain issued the ‘Penny Black,’ it followed suit with the ‘Twopenny Blue,’ which covered the double letter rate of up to 28 grams.

Service began on Jan. 10, 1840, and the reasons for the increased mail volume were many. In her 2009 book Posting It: The Victorian Revolution in Letter Writing, U.S. professor Catherine Golden details Britain’s 19th-century reforms, which also eliminated the “free frank” due to its widespread abuse within the postal system.

Golden, a Skidmore College professor, presented at the 2010 Winston M. Blount Postal History Symposium with a talk entitled “You Need to Get Your Head Examined: The Unchanging Portrait of Queen Victoria on 19th-Century British Postage Stamps.”

Citing Royal Mail archives, the Postal Museum records 863 million letters sent in 1870, when postcards were introduced, and nearly 1.3 billion letters a decade later.

The per-capita rate increased from three letters a year in 1839 to 19 letters a year in 1860, two decades after Britain issued the Penny Black.

It wasn’t all great. Despite its many successes, Rowland Hill’s reformed postal system faced criticism from some sections of Victorian society in Britain and abroad. Concerns centred on mail’s potential to bolster amoral behaviour, including affairs, gossip, political agitation and criminal offences such as blackmailing, all of which could be exacerbated by the anonymity offered by prepaid letters (similar to the issues stemming from Internet anonymity today). Other concerns focused on the monarch’s depiction: “Some gentlemen found quite distasteful that in order to glue the stamps, they should ‘lick the Queen’s neck’ – a matter of public debate and scorn in the England of the 1840s,” according to a 2013 thesis submitted to the European University Institute.

Definitive stamps refer to the regular, non-commemorative issues used for mail. While the postal service primarily aims its commemorative stamps at collectors, a country’s definitive issues serve the vital function of facilitating the payment of postal fees. The size and vertical format have remained the same on most British definitives since the first issues in 1840.

Check letters refer to the letters engraved in both bottom corners (and sometimes the top corners) of the Penny Black, Twopenny Blue and Penny Red.

Thanks Jesse for this interesting look at the world's first postage stamp. I look forward to the second part!