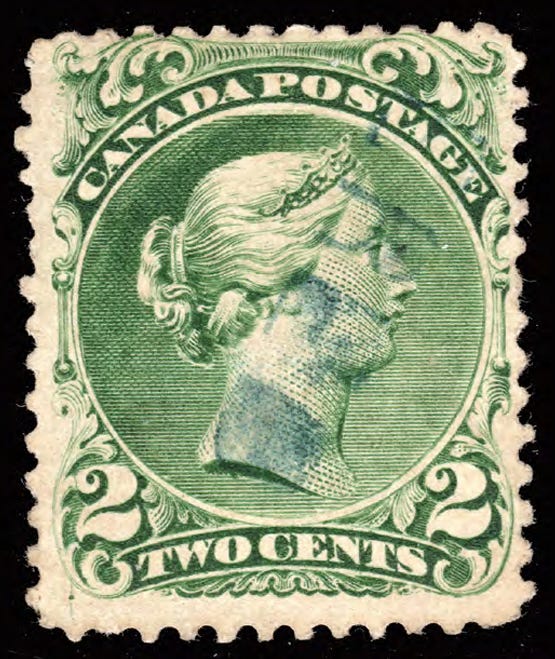

Canada's Large Queens gave us our rarest stamp

Canada’s rarest stamp, the 1868 two-cent Large Queen on laid paper, offers collectors three scant examples. They each cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, and the chance to buy one rarely arises.

This is the final story in a four-part series exploring the “Large Queens,” Canada’s first post-Confederation stamp issue. After more than 10,000 words (plus footnotes and cutlines), we’ve covered topics as diverse as global politics and national identity; Stoicism and Terence McKenna; Wicked and Nazi Germany; Marshall McLuhan and Noam Chomsky; and of course, philately and power.

You’ve now reached the beginning of the end. With it comes a celebration of extravagance, decadence and indulgence akin to the end of the Roman Empire, a society whose key issues paled in comparison to the selfish desires of the sloppy elites. (“History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.”)

Below, we’ll explore Canada’s rarest stamp – the 1868 two-cent Large Queen on laid paper – and then conclude with the Post Office Department’s transition to the follow-up Small Queen issue. (For a recap of the series, check out parts one, two and three.)

Mostly printed on common wove paper, the extant stamps from Canada’s Large Queen series include a select few examples printed on extremely uncommon laid paper, an identifying feature of the country’s rarest issue.1

The British American Bank Note Company printed some of the series’ one-, two- and three-cent stamps using laid paper. All of the existing examples, including the three known 1868 two-cent Large Queens on laid paper – Canada’s rarest stamps – feature horizontal laid lines.2

The latest sale of a two-cent Large Queen on laid paper came in November 2020, when long-time dealer Maxime Herold privately brokered a $345,000 deal for one of the three examples. It’s the highest price paid for the 157-year-old issue, meaning the stamp not only constitutes Canada’s rarest issue, but its selling price places it among the most valuable pieces of Canadian philatelic history.3

For the first time since 1993, the stamp once again belongs to a non-Canadian collector, an anonymous “foreign buyer” living outside of Canada, according to Herold.4

“It’s pretty big accomplishment – especially for that price – and it had to be hand delivered,” Herold told me in early 2021 for a story published in Canadian Stamp News.

As part of a condition of this sale, Toronto’s Vincent Graves Greene Philatelic Research Foundation certified the stamp as genuine, and Herold flew to the buyer’s home country to deliver the stamp in person.

After the Post Office Department issued the stamp in 1868, someone likely used it to mail a registered letter in the Hamilton area owing to the first five letters of a blue straight-line “REGISTERED” cancellation appearing over the queen’s face.5

Its provenance can be traced to France-born philatelist Philipp von Ferrary, the son of the Duke and Duchess of Galliera.6

Ferrary, who also once owned the 1856 one-cent magenta – the world’s rarest and most valuable stamp and after a 2014 sale the most expensive item by both weight and size – came from a family of influential bankers. His father co-founded the French banking company Crédit Mobilier, which financed many major construction projects in 19th-century Europe.

It’s unknown how the younger Ferrary came to own the two-cent Large Queen on laid paper, but its sale is widely reported.

In 1915, two years before his death, Ferrary bequeathed his collection – then the largest and most complete worldwide collection – to “the German nation” for display at a Berlin museum, The French government, however, eventually seized it as reparations following the First World War and auctioned it across 14 sales in 1921-24. The original three-volume catalogue spanned more than 1,000 pages.

Ferrary’s two-cent Large Queen on laid paper crossed the auction block in Paris on June 18, 1924, when U.S. dealer Warren Colson, of Boston, bought it for 2,510 francs (about $500 at the time). Offered as a group of Large Queens as Lot 53, it sold along with two other two-cent issues.7

After five owners and six sales – Saskatoon dealer John Jamieson acquired the stamp in 1993 and 1997 – Ferrary’s two-cent Large Queen on laid paper eventually made its way to Ontario collector Ron Brigham to join what Maclean’s called the “greatest collection of Canadian stamps ever.”

In August 2013, in the early years of a prolonged illness, Brigham also talked to Maclean’s about his philatelic legacy.

“I’m old,” he said. “I want to make sure I have the pleasure of seeing where they go.”

While his two-cent Large Queen on laid paper remained unsold after the 2014 sale of his landmark collection, Brigham hired Herold to find a buyer in 2020. He died two years later.

One of the other known examples – this one with a two-ring “5” numeral cancel and also used in Hamilton – arrived on the philatelic market in 1935 with the estate sale of English stamp dealer J.W. Westhorpe.

“It resided in the Firth collection for decades until its sale in 1971, and it also has an unbroken provenance to the present day,” Toronto philatelist Glenn Archer, a noted Large Queen expert and a Greene Foundation expert, wrote in the January-March 2014 issue of BNA Topics. “It apparently resides in a major British Commonwealth collection in Southern California.”

The stamp is still believed to belong to California dealer and Colonial Stamp Company owner George Holschauer.

For nearly 90 years, collectors had just two examples of the two-cent Large Queen on laid paper over which to struggle in their mission to form a complete Canadian stamp collection.

It all changed in 2013, when U.S. collector Michael Smith famously found the third example in an American Philatelic Society stock book. Mistakenly offered as the common wove paper variety, the used stamp cost Smith about $60 plus the subsequent fee to the Greene Foundation, which, after extensive analysis, certified it as genuine.

“The discovery took me by complete surprise,” Smith told Canadian Stamp News in March 2014. “The first thought, even before I triple checked the stamp, was this can’t be. Then, after checking what I saw, I was in utter disbelief.”

“Then I guess my adrenaline jumped up pretty good as I had a strange tingly feeling and I couldn’t really settle down and take it all in. I was completely overwhelmed.”

Smith’s discovery prominently features a Canada West (CW) cancellation dated March 16, 1870, and reading “Hamilton / CW.”

“It is interesting to note that all three examples appear to have a Hamilton connection,” Archer added in his 2014 BNA Topics report. “The use of blue ink in Hamilton is well documented in the 1869/1870 period; I have personally seen several CDS (circular date stamps) and other hammer strikes in both black and blue ink.”

After Smith consigned his discovery to New Brunswick’s Eastern Auctions, it hammered down for $215,000 (plus buyer’s premium) in an October 2014 sale.

LARGE QUEENS PHASED OUT

As the public depleted Large Queen stamp stocks, the Post Office Department phased out most of the values in favour of the subsequent “Small Queen” issue, which first franked mail in January 1870.

Only the 15-cent Large Queen proved irreplaceable for a time; it remained on sale at post offices and in use among mail senders for more than 30 years.8

The series’ common portrait of Queen Victoria, the reigning monarch at the time of Canadian Confederation, symbolized the country’s colonial history while the stamp issue recognized the new dominion’s self-governing status. Despite the Province of Canada, a pre-Confederation British colony, previously celebrating on its first stamp an industrious beaver rather than a royal family member, the monarchy has remained a regular figure on Canadian stamps over the past 150-plus years.

For 29 years, every Canadian definitive stamp featured the same regal portrait of Queen Victoria, whose reign later provided the subject of Canada’s first commemorative issue in 1897, when she marked her 60th anniversary on the throne.9

At the dawn of the 20th century, with Queen Victoria in her 62nd year as Canada’s first monarch, she had played the lead role in most of the country’s stamp designs.

When the 21st century began, her descendant Queen Elizabeth II had been on the throne for 48 years, during which time many changes, including broadening the scope of stamp subjects, took place in Canadian philately.

In 1900, Victoria’s image was found on all Canadian stamps then in use. But on the eve of the current century, Elizabeth II only graced one of the current definitive stamps (the 46-cent domestic letter rate). While people continue to debate Canada’s ties to, as well as its need for, the system of constitutional monarchy, Canada Post continued its tradition of honouring the Canadian sovereign on definitive stamps with a King Charles III definitive stamp issued during his coronation in May 2023.

Along with the issues following it, the Large Queen series played a significant role in shaping Canada’s founding myths and upholding its historical autobiography, all while facilitating communication and commerce across the vast territories of the newly formed dominion.

With this four-part Large Queen series now complete, the next edition of Power & Philately will look at a different subject through the lens of a different stamp in early February.

P.S. Remember, subscriptions for Power & Philately are free. Subscribers receive an utterly luscious story in their inbox each week with full access to the archive of past stories plus Substack’s large reader community. While no payment is ever necessary to access Power & Philately, many righteous readers have opted to pay for donation subscriptions ($5 a month or $50 a year) or join the founding member plan ($100 a year) as “esteemed financiers.” Each of my esteemed financiers receives in the mail a special gift related to philately, propaganda or both.

The common wove paper features vertical mesh while the uncommon laid paper features horizontal mesh. Because you may work in an industry unrelated to pulp, paper or printing processes, I’ll try to explain mesh for you. The paper-making process includes three phases.

Firstly, the papermakers prepare the pulp as a suspension of fibers; secondly, they form the paper using wire mesh; and lastly, they finish and dry the paper's surface. In the late 19th century, stamp printers added laid lines by attaching wires perpendicular to the wire mesh carrying the pulp in the paper-making machine.

“The result is that by definition Large Queen stamps which show horizontal laid lines will measure as vertically meshed stamps because the laid lines were applied perpendicular to the flow of the mesh in paper production,” reads a March 2013 technical report published by Toronto’s Vincent Graves Greene Philatelic Research Foundation.

Altogether, the eight different Large Queen denominations exist on 11 paper types used between 1868 and 1872. Aside from their mesh and lines, the papers differed by thickness, texture, transparency, porosity and colour.

The stamps’ laid lines originate from the printing process, in which wires created visible lines in the paper.

In its March 2013 technical report, the Greene Foundation’s expert committee confirmed the discovery of the third known 1868 two-cent Large Queen on laid paper.

“Committee members (Garfield) Portch, (Rob) Taylor and (Ted) Nixon spent a day with Richard Gratton understanding papermaking in the latter part of the 19th century, how pulp was applied to a wire mesh or screen, and how wires could be added to the wire mesh to create visible laid lines in the paper.

“The wire mesh on the paper-making machine is stretched and flows in a large loop and carries the pulp. We understand that all paper has a mesh. The mesh visible within the paper runs in the direction that the wire mesh runs in the machine. Looking at this lengthwise down the wire screen, the mesh will appear to run away from you or run vertical as opposed to having a horizontal prominence running across in front of you.

“Whether the paper as viewed on a printed stamp has a vertical versus horizontal mesh has nothing to do with production of the paper. It only indicates the direction that the paper was fed into the printing press.”

The British American Bank Note Company printed the Large Queen stamps on damp paper, which slightly shrunk across the grain of the mesh during production. The stamps feature either horizontal or vertical mesh with varying degrees of strength. Looking at examples of the same Large Queen denomination, stamps with vertical mesh measure about 0.3 millimetres taller and narrower than ones with horizontal mesh.

“This is a very important feature,” adds the Greene Foundation report.

New Brunswick’s Eastern Auctions set an auction record last March, when a mint pair of 1851 Queen Victoria 12-penny black stamps hammered down for $625,000 ($740,625 with the buyer’s premium), the highest price paid for a single lot at a Canadian philatelic auction. Eastern also set the previous record a year earlier, in March 2023, when the firm auctioned Sir Sandford Fleming’s three-pence “Beaver” essay for $475,000 ($562,875 with the buyer’s premium).

Despite these substantial sums, they fall far short of the highest known prices paid for philatelic items worldwide.

The current record price for a single stamp stands at $9.48 million US (about $10.33 million Cdn.), about 15 times more expensive than Canada’s $625,000 “12-Penny Black.” U.S. shoe designer and philatelist Stuart Weitzman paid that staggering sum in 2014 for British Guiana’s unique 1856 one-cent magenta stamp. It is, of course, the only known example, and it’s generally considered the world’s rarest and most valuable stamp. (Its 2014 sale also made it the world’s most expensive item by weight and size).

The stamp’s current owner, U.K. firm Stanley Gibbons, which acquired it in 2021, has since achieved its goal to “democratise” the world-renowned rarity using fractional ownership. The scheme has seen collectors and investors purchase more than 40,000 pieces of the stamp turned stock market-style equity units, the remaining 49 per cent of which (about 39,000 pieces) Gibbons owns.

More recently, in 2021, a German firm sold a rare 1847 Mauritius Ball cover, one of just three extant examples, for €8.1 million (about $11.9 million Cdn.). It’s believed to be the highest price ever paid for a single philatelic item.

In March 1993, Saskatoon dealer John Jamieson, who acquired the 1868 two-cent Large Queen on laid paper earlier that year, sold Canada’s rarest stamp to U.S. collector Robert Darling Jr., the man behind the “Bayfield Collection.”

In 1868, with Canada’s letter rate at three cents and its registration fee at two cents, a registered letter would’ve cost five cents to mail.

An Italian noble title with ties to the country’s aristocrats and originally created by Napoleon, Galliera refers to the town of the same name in Emilia-Romagna, a expansive region in northern Italy also home to the cities of Bologna and Parma. Philipp von Ferrary’s father Raffaele, a wealthy banker who invested in Europe’s Europe’s colonial expansion, received the Galliera title in 1838 at the behest of Pope Gregory XVI. But upon his death in 1876, his son refused to inherit neither his vast fortune nor his title of duke, to which the younger Ferrary was entitled.

Some historians debate the parentage of Philipp, who eventually renounced all of his family’s titles and (slightly) changed his surname from Ferrari to Ferrary, which he used on his calling cards, according to a December 1987 report in The American Philatelist by U.S. philatelic scholar and “masterful raconteur” Stanley Bierman.

One of the three examples offered in the June 1924 Ferrary Collection sale was used, owing to its cancellation, and printed on laid paper (described in French in the auction catalogue as “dont un obl. (obliterated, or cancelled) sur paper vergé.”

Another 15-cent value only appeared in Canada in 1897 with the the country’s first commemorative issue, which marked Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee – the 60th anniversary of her reign – and included this denomination.

“In this connection a proposal has been made and an agitation started for the issuance of a commemorative set of postage stamps and coins by the Dominion government, and a few of the reasons seem well worthy of consideration,” reads the Feb. 18, 1897 edition of the Qu'Appelle Progress. “The advocates of a new issue claim, and with a great deal of reason, that the present stamps are by no means up to the requirements of the people, or up to the present standard of stamps as issued by other countries. No change has been made in the general design or colour of Canadian stamps since 1871, and they therefore lack all the improvements of engraving and printing that have been brought out since that date.”

The Qu'Appelle Progress report also cites another “great cause for complaint against the present issue,” the Small Queen stamps, focusing on its colours.

“More people than it may be generally imagines are afflicted with colour blindness, and the present indefinite shades of many of the commoner stamps are a source of much trouble and annoyance.”

Another “defect,” according to the report, “is the small figuring,” a format to which the Post Office Department transitioned after first issuing larger stamps (the Large Queens) in 1868.

“All stamps of modern design have figures that are a prominent feature that will catch the idea first glance. … It has been suggested that the new stamps be made … larger than the present ones; and that the colours and figures of value be made more pronounced.”