Stamps tell Canada's complex story

Since before Canada gained self-governing independence in 1867, its officials have taken advantage of stamps' small yet aspirational nature to promote the many myths of the Canadian nation.

This is the first story in a multi-part series exploring Canadian stamps as propaganda—from the first issue in 1851 through the present day. This subseries will conclude my overarching Power & Philately introduction series, which began in early January with the first story providing a general overview of the newsletter’s concept. (As a reminder, I’m cooking up a combination of philately with a wider definition of propaganda, one which includes general nation-building and myth-making endeavours with both positive and negative connotations.) A week later, the second story looked at the postage stamp’s myth-making cousin, coinage, which has for millennia touted its issuers’ nation-building narratives. Later in January, the third story introduced stamps as propaganda with a look at Australia’s first issue. In February, the fourth and fifth stories travelled back to Victorian-era Britain for the world’s first issue, the Penny Black, which set the stage for stamps as national storytellers.

Now, “without further gilding the lily and with no more ado,” these next few stories will (finally) conclude my long-winded introduction series with a look at Canada’s take on philatelic propaganda.

Since even before Canada became a country, politicians have taken advantage of stamps’ small yet aspirational nature to promote the many myths of the would-be Canadian nation.

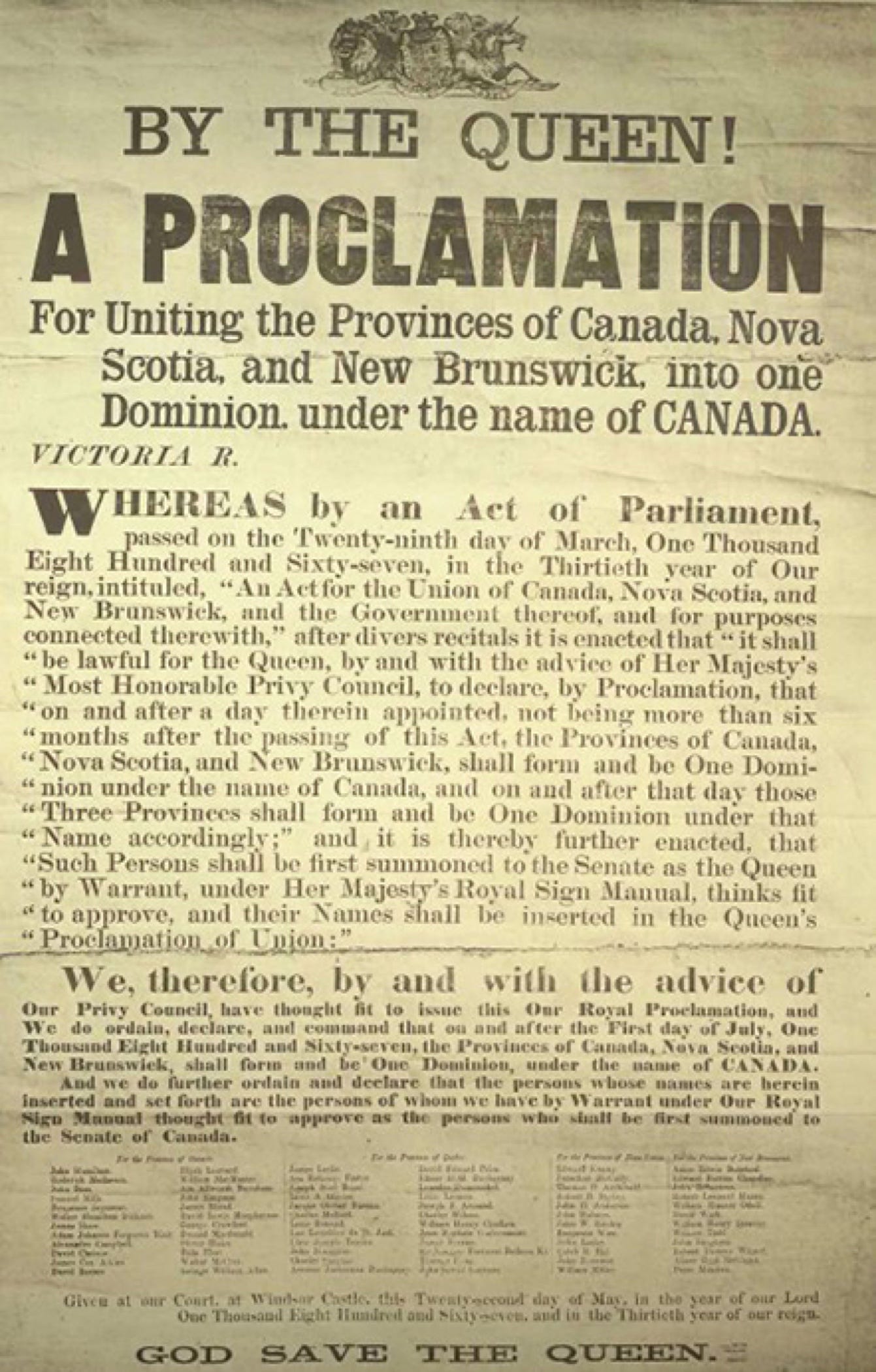

Like its Australian counterpart, Canada transformed from a British colony to a relatively independent nation within just a few decades of debate among imperialists and nationalists.1 Canada’s time came during the halcyon days of the mid-19th century with Confederation providing its dominion status in 1867. Despite its former colonial status, held for more than a century before gaining self-governing independence,2 Canada long mirrored “Mother Britain” in its use of stamps as nation-building tools.

In 1851, three of Britain’s North American colonies – the Province of Canada, Nova Scotia and then New Brunswick – issued the first stamps in what’s now the Dominion of Canada.3 Sweeping across the country and sometimes abroad, most of the nine designs featured royal or heraldic symbols. Two of the stamps depicted royal family members, including one with Queen Victoria and another one with her husband (and first cousin) Prince Albert, while six of them featured the queen’s crown alongside four heraldic floral emblems.

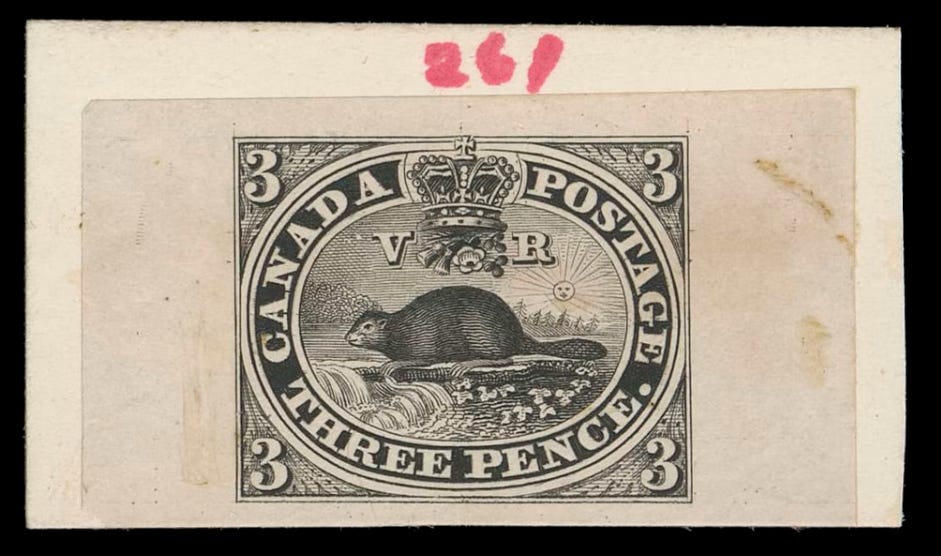

Just one of the stamps – now the most iconic of Canada’s first issues – used nation-building imagery to promote a distinctly Canadian idea. Centring on an industrious beaver, the unassuming red three-pence stamp, now known as the “Beaver” among collectors, represented the soon-to-be nation’s distinct character in the face of its colonial upbringing—a teenager rebelling as it came of age.

While the higher-value 12- and six-pence stamps featured the queen and her cousin-turned-husband, respectively, the low-value Beaver proved to be the most widely used – and indeed the most remembered – stamp among Canada’s first issues.

THE BEAVER LEADS THE WAY

The Beaver’s central design rejected a tradition observed across the British Empire in the 11 years since the world’s first stamp, the Penny Black, emerged from the motherland.

Scottish-born engineer-turned-inventor Sandford Fleming produced something “quite revolutionary,” according to James Bone, a philatelic archivist at Library & Archives Canada (LAC): it marked the first stamp to use an animal – not a monarch or a head of state – to symbolize a country.

“The beaver image simultaneously represented the industriousness and tenacity of the nascent Canadian nation in building up their cities, towns and communities while also harkening back to a time when beaver pelts were a common currency in economic activity,” Bone wrote in a 2017 LAC blog post.

The beaver played such a central role in Canada’s development it became an official symbol of Canadian sovereignty in 1975. Similar to other domestic trade items – lumber, ore, electricity and natural gas – beaver pelts provided people with modern, sometimes luxurious, products while serving as pillars of trade. Today, the beaver continues to appear on the country’s crests and coins.4

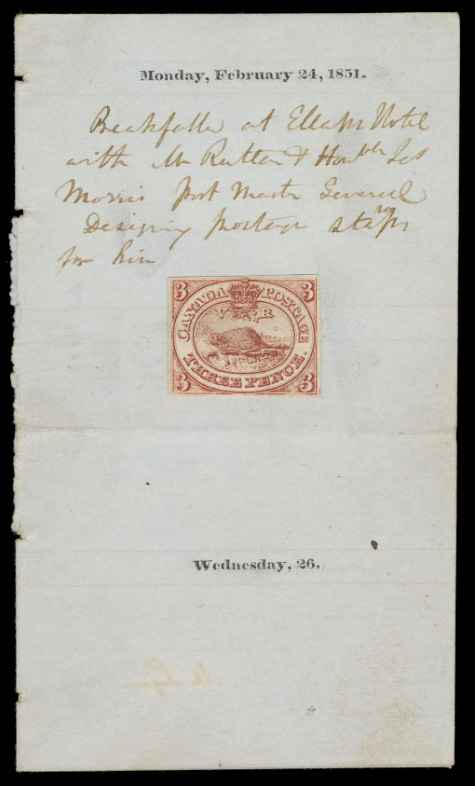

Then only 24 years old and having recently arrived in Canada from Scotland, Fleming met with Postmaster General James Morris, the first person to hold that position with the Province of Canada, in February 1851. In just two months, the duo would bring Fleming’s concept to life.

Fortunately for posterity, Fleming kept a diary of his daily activities, and an entry dated Feb. 24, 1851, detailed his meeting with Morris at the former Ellah’s Hotel on King Street West in Toronto.5

“Breakfasted at Ellah’s Hotel with Mr. Rutten and Honble. Jas Morris Post Master General designing postage stamps for him,” Fleming wrote.

Of significant interest to philatelists, Fleming’s son removed the page from his father’s diary in 1934 and traded it “for unspecified goods and services” to dealer H. Borden Clarke, according to Bone’s research.

Clarke valued the page at $10,000 – about $200,000 today adjusted for inflation – and promoted it with a limited run of 100 prints made with an early photocopier called a Photostat. It’s possible he discussed selling the page to the federal government, but the start of the Second World War stymied any negotiations, Bone added.

In 1941, Clarke reportedly sold the page to Ottawa collector Bruce Robson for $200. Robson then held the page until a 1996 auction, where an anonymous U.S. collector acquired it for $55,000 US.

More recently, acclaimed exhibitor Ron Brigham – Canada’s first and so far only international exhibiting champion – acquired the page at a 2004 Charles G. Firby Auctions sale for $110,000 US. Brigham, who died last August, held the page in his collection for the rest of his life.

Another name will join its provenance6 when the iconic piece of Canadian history crosses the block via Eastern Auctions later this month. On March 17, the page will open the first of four Brigham Estate sales with an estimate of $150,000.

A BUSY BEAVER UNDER A SMILING SUN

Fleming’s design centres on the beaver, shown in a left-facing profile at work on its dam.

The beaver stands atop a waterfall and flowers with a pine forest in the background and a smiling sun looking down on the scene. The imperial crown sits above the beaver on a group of heraldic flowers – the rose for England, the thistle for Scotland and the shamrock for Ireland – framed by the letters “VR,” referring to “Victoria Regina” (or Queen Victoria).

The stamp’s three-pence face value paid the domestic rate for letters weighing up to half an ounce.

Fleming also designed the six-pence stamp, which sent heavier letters or serviced North American destinations, and the 12-pence issue, which serviced foreign destinations.7

Across the country and around the world, these well-travelled bits of paper propaganda disseminated a new image of Canada, one primed to become a global soft power in the following century.8

The next story in this Canada-focused subseries, which concludes the Power & Philately introduction series, will explore the first stamps issued under the banner of the newly formed dominion—the 1868-76 “Large Queen” series. The eight stamps each feature a right-facing portrait of Queen Victoria, whose image became a central motif of Canadian definitive stamps for the next three decades.

In chapter four of his 2016 open textbook Canadian History: Post-Confederation, award-winning historian John Belshaw explored the “vocal debate among Canadians about empire and nation. … The imperialist view called on strong pro-British sentiments that echoed the ordeals of the Loyalists of 1783, and the defence of British North America against the United States in 1812 and 1866; the nationalists invoked the accomplishments of the voyageurs and the Hudson’s Bay Company, the native political traditions embodied in the rebellions of 1837-38, and the peculiar, dual cultural qualities of Canada.”

While Canada became a self-governing dominion with Britain’s 1867 passage of the British North America Act (also known as the Constitution Act), it only became wholly independent in 1982, when the British Parliament approved the Canada Act.

The Province of Canada issued three-, six- and 12-pence stamps in April, May and June 1851 featuring the now-iconic beaver, Prince Albert and Queen Victoria, respectively. Later that year, in September, Nova Scotia issued the world’s first diamond-shaped stamps in three-, six- and 12-pence denominations, all featuring the queen’s crown surrounded by four heraldic floral emblems. A week later, New Brunswick followed suit with a set of three diamond-shaped stamps in the same denominations and with nearly identical designs.

Since 1937, English artist G.E. Kruger-Gray’s beaver design has graced Canada’s five-cent circulation coin. The Royal Canadian Mint has also featured beavers on many collector coins (also known as non-circulating legal tender).

In a January 1888 letter to Postmaster General James Morris’s son, Sandford Fleming recounted this seminal moment in Canadian philately: “I duly received your note enclosing one of the early three-pence postage stamps which you have so kindly forwarded for my collection. I think I mentioned to you that I have in my possession the proof of the first postage stamp issued in Canada. It is now before me in my scrap book and I shall copy, on the other side, the explanation written with it. ‘This is the first proof from the plate of the first postage stamp issued in Canada designed by Sandford Fleming for the Post Master General, the Hon. James Morris, Toronto February, 1851.’

“You ask me to inform you of the circumstances. I was then a young man about 24, ready for anything whatever. I had been making designs of some sort for Sheriff Rutten, an intimate friend of your father. Your father had, in conversation, mentioned what he had in view with the issue of three-pence postage stamps. The Sheriff referred him to me as a person who would make a design. I was sent for and was introduced to your father one morning at Stone’s Hotel (author’s note: Fleming mistakenly references Stone’s Hotel despite him and Morris meeting at Ellah’s Hotel) on King Street, now occupied by the Romain Building. According to my recollection you were present, 37 years younger than you are now. The design was made, engraved approved and used for years. The first proof taken from the plate by the engraver, is as I have stated in my collection of scraps. Wishing you a happy new year and all other good things.”

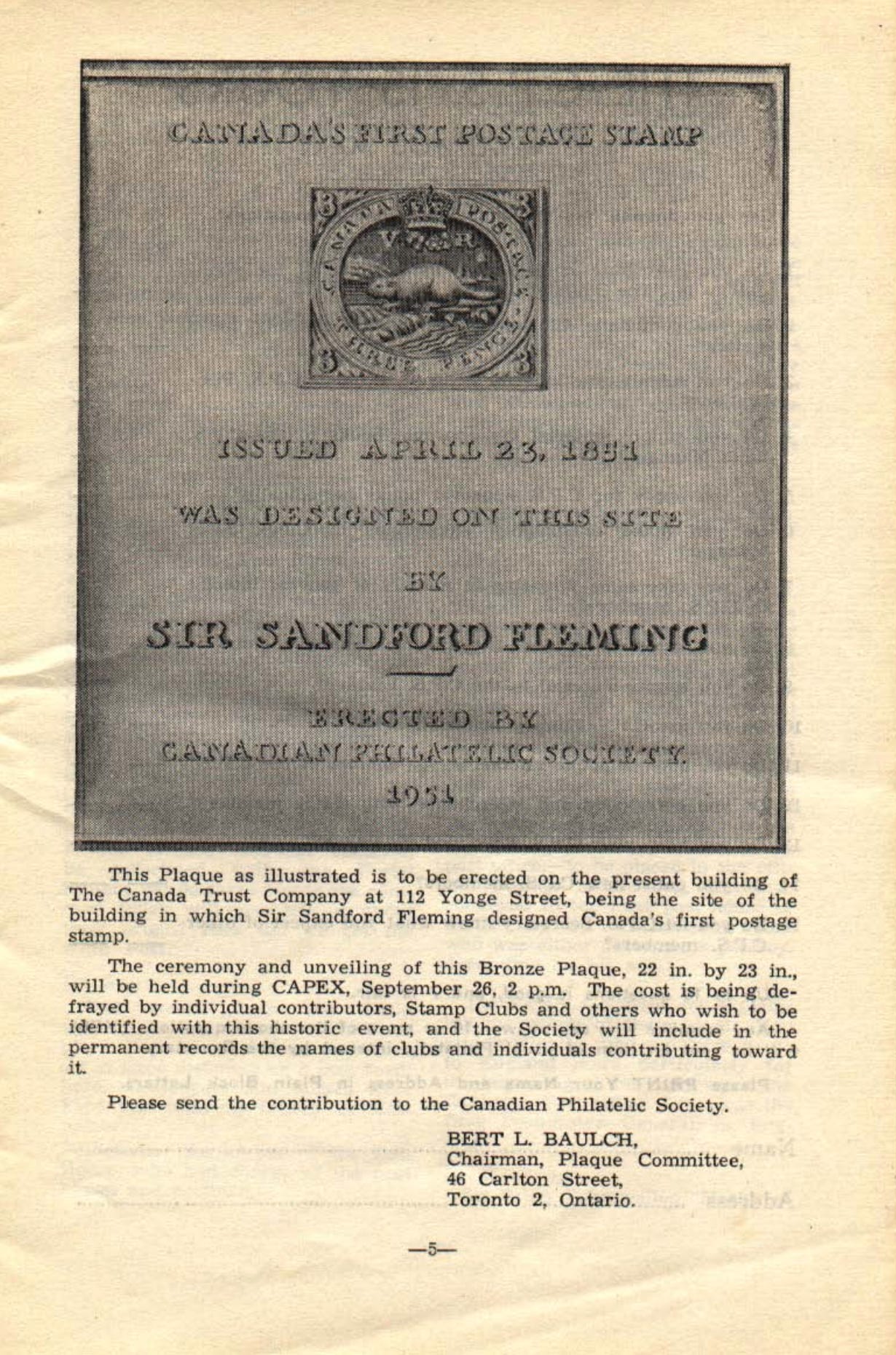

A century later, in September 1951, members of the Canadian Philatelic Society (now the Royal Philatelic Society of Canada) mounted a plaque at the Canada Trust building at 112 Yonge St. in conjunction with CAPEX 51, Canada’s first international philatelic exhibition. The address was believed to be the site of Ellah’s Hotel, where Fleming met with Morris a century earlier; however, Ellah’s Hotel stood around the corner on King Street West as noted in Fleming’s 1888 letter. The plaque remains on a pillar outside the current Yonge Street building’s east-facing entrance.

In a 2017 Forbes column, lifelong U.S. philatelist Richard Lehmann, who often writes about philatelic investing, explained provenance as “the earliest known history of something. In more modern usage it refers to the record of ownership of an object of art or antique as a guide to authenticity or quality. Since the 1950s when marketing became a recognized business discipline, provenance has evolved into one of the most powerful marketing tools on the planet. The very term provides a cachet or stature to items with a value that is hard to define. It accounts for why investors will pay tens of millions of dollars for an artwork that most of us wouldn’t give a second thought to if offered to us for $20 at a flea market. In fact, finding such an item at a flea market becomes a part of its provenance because it makes such a good story. Philately is full of such stories.”

The website of late postal historian Andrew Liptak, known as “Philcovex” on his Postal History Corner blog, now managed by the Postal History Society of Canada, offers an extensive list of pre-Canadian postal rates in 1851.

The first issue released after the Dominion of Canada’s formation in 1867 came a year later, in 1868, later with a seven-stamp definitive series featuring Queen Victoria, a central motif of Canadian stamps for the next three decades.

“Early Canadian stamps displayed a strong connection to the British Empire while simultaneously championing a bi-cultural French–English characterization of Canada,” Canadian researcher Michael Maloney wrote in a 2013 article for Material Culture Review, Canada’s only peer-reviewed scholarly journal dedicated to material culture.